JOSEPH NDANDARIKA: A SANGOMA’S APPRENTICE WHO BECAME A GURU IN STONE SCULPTURE AND PAINTING – 01/03/2023

How Ndandarika Unleashed the Spirit In Stones

JOSEPH NDANDARIKA: A SANGOMA’S APPRENTICE WHO BECAME A GURU IN STONE SCULPTURE AND PAINTING

How Ndandarika Unleashed the Spirit In Stones

By Kamangeni Phiri

RENOWNED sculptor, the late Joseph Ndandarika, was a rare breed of an artist who was equally at home painting canvass, carving wood or stones.

Indeed, Ndandarika was recognised as a genius by those who had the privilege of working closely with him since he could express his talent using any imaginable art medium.

National Art Gallery’s first director, the late Frank McEwen, described Ndandarika as, “a great and universal genius who worked fluently in every possible medium.”

That lack of inhibition became the basis for Ndandarika’s self-confidence as a skilled and competent artist. His art pieces were a reflection of his self-belief and attention to detail.

The man had a midas touch – whatever art form he laid his hands on became a collector’s dream item.

It was, however, his stone sculptures that gave him world fame.

But there is no great genius without some touch of madness, as once pointed out by the immortal Greek philosopher, Aristotle.

Ndandarika, a hardcore traditionalist, prevented his equally gifted wife, Locardia, from pursuing her dream career of stone carving for fear that she could be exposed to many men.

The late sculptor was a traditionalist who believed that a woman’s place was in the kitchen.

Locardia, who died in January this year, is on record saying her former husband did not want her to touch his tools.

“He told me, I didn’t marry you for doing such things, I want you to look after my children,” she said in one of her archived interviews.

This created friction between the two resulting in their eventual terminating their 14-year old marriage in 1978.

That Ndandarika turned out to be a traditionalist was no big surprise. He was a grandson of a highly respected inyanga/n’anga. Ndandarika at one time even undertook some training to become a traditional healer.

In his works, he was primarily inspired by his everyday life, the love, pain and joys of everyday life. He also drew inspiration from the relationship between man and animals, among other things.

“He was known for his impressive, narrative figurative sculptures that embodied physical depictions and descriptions of Shona people, animal life and the Shona belief system. The supernatural was also an important theme in his work.

However, not all his work, was based on traditional beliefs and mystic; many depicted everyday life, the bonding between man and animal, friendship, love, maternal and filial bonding. Throughout his vast creativity and output, Ndandarika was always searching for new themes and new postures to articulate African culture and traditions,” wrote Zimbabwean Art Consultant, artist and lecturer, Dr Tony Monda in his profile of the artist published by The Patriot in 2015.

Ndandarika was not your ordinary sculptor who donned overalls covered in stone dust everytime. He always turned out in formal designer suits, giving the impression of a successful businessman.

Despite his slightly built frame, Ndandarika spoke with authority as writer Monda found out when he was assigned to interview the late sculptor in 1989.

He was greeted by the statement: “I am the great Shona sculptor Joseph Ndandarika – who are you?”

The question was probably mere rhetoric designed to unsettle Monda while Ndandarika subtly marked his territory. It was the ‘I am in charge here’ kind of statement packaged in the form of a question.

But beneath the authoritative voice and sartorial dressings lay a humorous warm-hearted intelligent man.

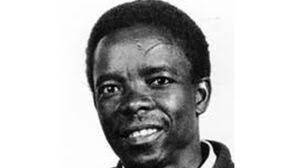

Joseph Ndandarika was born in May 1940 in Harare. He was a Zimbabwean sculptor known for his figurative works and he grew up in Rusape. The artist’s father was a Malawian who was employed as a bus driver.

Ndandarika was exposed to art at an early age through his talented grandmother who used to make clay pots for brewing traditional beer. He developed his art skills through clay moulding following in the footsteps of his grandmother.

His mother was also artistic as she occasionally worked as a model for Rusape-based sculptor, Job Kekana.

Ndandarika went through primary school and attended a Catholic boarding school at Serima Mission in the late 1950s.

His natural talent in art was quickly identified at the mission school by Father John Groeber and Cornelius Manguma, who went on to train him in drawing and woodcarving. Fr Groeber also chose Ndandarika to paint several murals inside the St. Mary’s church.

In 1959, he relocated to Salisbury, now Harare. The following year, in 1960, Ndandarika joined Frank McEwen‘s Workshop School, marking the genesis of his rise to world fame.

He became one of McEwen’s leading painters, specialising in landscapes and witchcraft scenes. At the height of his painting career in 1962, Ndandarika did an outstandingly beautiful oil painting titled “Bushmen Running From the Rain” that was acquired by one of the biggest art museums in the world, Museum Of Modern Art (MoMA) based in New York. His hallmark approach was mixing paints on the canvas rather than on the palette, which resulted in a highly uneven surface.

After several years of painting, McEwen was bowled over by Ndandarika’s talents as a painter. He sent the talented artist to train in stone sculpture with the legendary late sculptor, Joram Mariga.

Ndandarika fell in love with stone sculpting and within a short time he, again, proved his ingenuity in this art genre. He gradually shifted more and more towards sculpting during the mid-1960s, ending up featuring in all of McEwen’s major exhibitions that made Zimbabwean stone sculpture famous.

Ndandarika’s name will remain etched in Zimbabwe’s art history records as the man who convinced McEwen to unlock the value in local stone sculpting. He told Rhodesia’s first art gallery director that in Shona mythology, spirits inhabited rock formations and this had a major impact in McEwen’s marketing of Zimbabwean sculpture. McEwen told the world that his sculptors were, “unleashing the spirit in the stone in the course of their work.”

Thus, the term, ‘Shona Sculpture’ was born.

The going got a bit tough for all sculptors in the country when McEwen left Rhodesia around 1973 for England.

But Ndandarika was able to keep selling through those hard times of the 1970s. During the 1980s Zimbabwean arts revival he had become one of the country’s most prominent “first generation” sculptors.

Ndandarika married Locardia in 1964 and got divorced in 1978 mainly because of disagreements over women’s participation in sculpting. Two of the couple’s children, Ronnie Drigo and Virginia Ndandarika, are also artists. Ndandarika also mentored a number of artists, including Jonathan Mhondorohuma.

Joseph Ndandarika died tragically in May 1991 at the age of 50.

His death was devastating to Zimbabwe’s arts community. In Ndandarika, the country lost one of its most gifted and successful sculptors, widely regarded as one of the world’s best.

If stones could talk then Ndandarika’s pieces would certainly do that.

Here was one artist who could portray the experiences and dilemmas of life, capturing the love, the anger, the hate, the laughter and happiness of our everyday lives. The artist has featured in solo and group exhibitions and his works, which won him many awards, have been exhibited and collected worldwide.

Joseph’s great name will always be celebrated in pieces such as kupfugamira vakuru (kneeling as a sign of respect), kutyora mizura) (genuflecting.), kuombera,(clapping) – all reflecting the cultural body gestures and postures of traditional Shona etiquette. His art confirmed that the core of Zimbabwean social and traditional values remained unaffected by urbanisation.

One of Ndandarika’s outstanding sculpture pieces was Telling Secrets. It was depicted on a Zimbabwean stamp issued to commemorate Commonwealth Day on 14 March 1983. The stamp formed the 11cents value in a set completed with works by Henry Munyaradzi, John Takawira and Nicholas Mukomberanwa.

For Ndandarika to get the opportunity to shine as a painter at McEwen’s studio he had to hide his background of having many years of training at a Christian institution, Serima Mission. McEwen preferred to work with untrained, pagan artists. It was during the same time that Ndandarika revealed he was the grandson of a sangoma further alleging he had undergone extensive training under his grandfather. The artist who joined McEwen’s Studios as a Roman Catholic later converted to his traditional religion to fit the pagan bill.

But was Ndandarika really a bona fide traditionalist or someone who was just trying to fit into a system that preferred working with non Christians?

We will never know.