Jerusarema Mbende : Eroticism or a Viable Cultural Vehicle?

Douglas Vambe

By Kamangeni Phiri

SINCE time immemorial, traditional dancing in Zimbabwe has played an important role in promoting and sustaining local culture, tradition, spirituality and history.

The dances are numerous and varied, but they all reflect the rich culture of the people they represent, even if they have evolved over time.

None, however, does it better than Mbende Jerusarema, a traditional dance inspired by a mole or a mouse when burrowing the ground for food or shelter.

It is popular among the Shona’s Zezuru ethnic group who live in Mashonaland East’s Murehwa, Uzumba, Maramba, and Pfungwe districts, in Zimbabwe’s north-eastern region.

The dance is seemingly seductive as it is full of acrobatics, gyrating and hip movements by women whose dance moves are in unison with their male counterparts’. It culminates in the energetic thrusting of the pelvis directed towards each other by both dancers, causing exhilaration among the audience.

Alfred Chiyangwa, a dancer and manager of Ngoma Dzepasi Mbende Dance Group, which is based in Fungai Village in Mashonaland East, told journalist Daisy Jeremani writing for TOPIA that the dance also depicted love between couples. During the dance, the locking move at the end of the routine highlights the ultimate coupling of lovers.

“From my years of practicing it, I have come to discover that the dance shows the hard work of the father for the sake of his wife and children – and then after the hard work how they enter their bedroom for intimacy,” he said.

It is such movements which made the dance unpopular among the missionaries who dismissed it as sexually explicit and suggestive.

Jesmael Mataga a Zimbabwean scholar based in South Africa posits in his paper titled, Beyond the Dance: a Look at Mbende (Jerusarema) Traditional Dance in Zimbabwe, that white missionaries saw Mbende as licentious, indecent and provocative, and collaborated with the Native Commissioners to ban the dance which they regarded as a hindrance to conversion of the locals to Christianity. Due to its popularity, he further argues, the dance also angered the early white settlers who were facing challenges in recruiting African labour for the farms and the mines. Mbende was eventually banned in 1910 in terms of the Witchcraft Suppression Act of 18 August 1899.

Despite the ban, Mbende refused to die.

The dance reinvented itself as Jerusarema, a name deliberately picked by the traditional leadership to make it more acceptable to the Christian world. Historians say a play accompanied by Mbende Jerusarema dances celebrating the birth of Jesus Christ was also performed by locals as a way of placating the missionaries. In the play, Jesus’s birthplace was erroneously given as Jerusalem instead of Bethlehem. The error was understandable, given that Christianity was still in its infancy then. From that time the dance assumed the new name of Mbende-Jerusarema. Today, both names are regularly used.

However, Mataga says, despite the onslaught of colonialism, Christianity and westernisation, traditional dances like Mbende Jerusarema have survived to this day, albeit with modifications.

“It was the banning which necessitated the change of name to make it more acceptable. The changing lifestyles caused by urbanization also altered the way it was performed. It seems that while certain performers modified the dance to please the white settlers by taking away those movements perceived to be unacceptable, another change seen by the local community as a distortion was taking place in the towns. Due to increasing urbanization from the 1920s onwards, Jerusarema was often performed for recreation in the township bars and beer halls,”said Mataga.

Mbende Jerusarema dance is, today, influencing emerging dance groups like Hohodza, who mix the traditional beat with modern instruments. Despite the missionaries’ censure, the dance remained popular in Zimbabwe and became a source of pride and identity in the resistance to colonial power.

The dance is an important cultural expression and in 2005 it was deservedly among 43 such expressions from around the globe proclaimed on the UNESCO Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible heritage of humanity list, making it one of the few African cultural expressions accorded such recognition.

The list acknowledged the dance as a crucial living cultural heritage that is fragile and perishable, but essential for the cultural identity of the community. Other notable performances listed from the Southern African region include the Makishi masquerade from Zambia, the Vimbuza healing dance from Malawi and Gule Wamkulu (Zambia, Malawi and Mozambique).

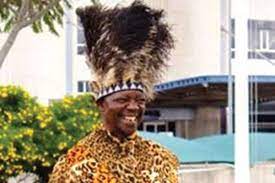

A proponent of Mbende and renowned master drummer, the late Douglas Vambe, was one of the chief informants during the compilation process for the UNESCO candidature file for the nomination of Mbende Jerusarema.

Traditional dances and performances, such as Mbende Jerusarema remain vital in Zimbabwe’s socio-economic and political systems. They are performed in a variety of settings and command respect from local communities. Reasons for performing traditional dances are many and varied. Popular belief has it that the Shona used Jerusarema as a battle dance and a diversionary technique during military encounters.

The dance can also be performed at weddings, festivities, recreational competitions, funerals, and political meetings. Jerusarema has been performed in three eras of Zimbabwean culture, that is, pre-colonial (before 1890), colonial (1890 to 1980), and post-colonial (from 1980 to-date). It is believed that Jerusarema/Mbende began as a military dance, fertility dance, hunting dance, and death dance. This demonstrates that the Zezuru community used Jerusarema dancing for ritual purposes.

Jerusarema Mbende was also used as a courtship and ceremonial dance. Young boys and girls adopted the dance at evening gatherings during a full moon, referred to as jenaguru in Shona.

Boys and girls would dance in pairs and eventually court each other through song. One such song was the popular Sarura Wako in Shona, which loosely translates to “choose your partner.”

A Jerusarema dancer’s skill on the dancing arena were and still is anchored on the expertise in drumming of the drummer. Drumming as an art requires intricate skills, strength and mental alertness. The drummer – just like the one who plays the lead drum (mbarure) for the Gule waMkulu dance – must always be attentive to everything that is happening in the dance arena. This is why at times he doubles up as the dance instructor.

It is the master drummer who gives form to the captivating sound of the Mbende beat. One master drummer would perform the music accompanied by clappers, rattles, and costumes. Drumming, singing, clapping, and rattle playing combine to create a polyrhythmic sound that propels the dancers forward. There are two main areas of activity during the dance: a line of musicians who are constantly playing the beats, and a group of ladies and men who take turns dancing.

A majority of the material objects needed by the dancers can be divided into two: clothing and musical instruments. The most noticeable instrument in making the music is the “mutumba”, which is a drum made from the “mutiti” or the “mutsvanzwa” tree known botanically as pseodolanchnostylisis maprouneifolia. This is a rare yet well-protected indigenous tree that was chosen for its high quality wood, strength and hardness, and excellent resonance capabilities.

To create a well-coordinated beat with the singing and drumming, Jerusarema traditional groups use wooden clappers (maja/manja) as instruments. The strength of hard wood trees like the mutara tree (Gardenia spaturiflora) is often chosen to make the wooden clappers manja. This is necessary to endure the constant impact of clapping on the wood.

For dancing outfits, the second most important type of Mbende Jerusarema material item, groups would wear traditionally made animal skins. Leopard, monkey, cheetah, and wild cat skins were often used to make the outfits as their leather is flexible, comfortable to wear, and easy to work with.

On rare occasions, domestic animals’ skins, such as cattle, goats, and sheep are used, but the quality of these garments is far inferior to those produced from wild animal skins. But due to the influence of westernisation, the outfits have been modernized. Today’s dancers generally wear textile costumes blended with animal skins.

Naturally, the shift from traditional to more modern outfits and instruments affected the continuity of traditional knowledge, skills and the associated environmental knowledge. Also affected was the knowledge of craftsmanship and construction and conservation of traditional instruments and costumes. Fewer people use traditional drums and other instruments these days resulting in the reduced production of traditional instruments. The production of traditional costumes survived on good hunting practices and skills, the art of processing animal skins and constructing them into appropriate, comfortable, aesthetically appealing clothing. All this traditional expertise is under threat as the dancers opt for easy-to-buy, cheap, textile substitutes.

So Mbende Jerusarema is more than gyrating of the waist and drum beating, it is a lifestyle and an entire industry.

Ends